‘Astonishing’ study declares

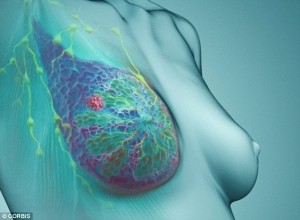

Scientists have discovered a gene which drives a fast-growing, aggressive form of breast cancer.

Terminal breast cancer has been wiped out, in ‘astounding’ research that raises hope of a cure for thousands of women with the disease.

In tests on mice, their cancer vanished completely for at least eight months.

This is the equivalent of 24 years for a woman and would be judged a lasting cure.

In contrast, current treatments extend life by as little as six months.

The US researchers said that even if even only partly as successful in people, it could transform the treatment of cancer.

Mauro Ferrari, president of the Houston Methodist Research Institute, said: ‘I would never want to over-promise to the thousands of patients looking for a cure but the data is astounding.’

However, British experts cautioned that what works in the lab doesn’t always help real patients and said much more research is needed.

Dr Ferrari’s focus is metastatic cancer, or cancer that has spread from the breast to other parts of the body, such as the lungs, liver or bones.

While the initial tumour that appears on a woman’s breast rarely kills, once the disease starts to eat away at other parts of the body it becomes incurable.

Drugs struggle to get to tumours hidden deep in the lungs or liver and once there, they risk being pumped out by cells that have become resistant to treatment.

Dr Ferrari, of the Houston Medical Research Institute, has found an ingenious way of getting round these defences – and so of potentially curing metastatic cancer.

He has taken a widely-used cancer drug called doxorubicin and packed it in microscopic discs made of silicon.

The silicon packaging hides the drug from the cancer, allowing it to sneak into its cells.

Once inside, the silicon is broken down, releasing the drug, which is in an inactive form.

The drug then moves out of reach of the pumps that are poised to eject it and towards the very heart of cell.

Once there, the drug is activated and the cell is killed.

In tests on mice with terminal disease, all the animals given conventional treatment died.

In contrast, half of the creatures given the new treatment were still cancer-free after eight months – roughly 24 years in human terms.

To put this into context, a woman whose breast cancer has spread to her lungs can normally expect to live for between six and 24 months.

Dr Ferrari says that in future, women with metastatic breast cancer could be given a jab of billions of drug-filled silicon discs into their arm.

This would home in on the tumours riddling their lungs or liver and destroy them.

He hopes to test the treatment on women for the first time next year and says that some of the early drug trials could be in the UK.

The researcher said: ‘If this research bears out in humans and we see even a fraction of the survival time, we are still talking about dramatically extending life for many years.

‘That’s essentially a providing a cure in a patient population that is now being told there is none.’

Writing in the journal Nature Biotechnology, he added he had only tried the technique against one type of breast cancer but he is optimistic it will also work against other types of cancer.

He said: ‘We are talking about changing the landscape of metastatic disease, so it’s no longer a death sentence.’

Baroness Delyth Morgan, Chief Executive at Breast Cancer Now, said: ‘While the results look promising in mice, there is still a long way to go before we will know if this technique could be an effective treatment for women.

‘Metastatic breast cancer sadly still cuts short nearly 1,000 women’s lives in the UK each month.

‘We must find ways to stop the disease in its tracks and we’re keen to see the results once this technique is trialled in patients.’

Dr Alan Worsley, of Cancer Research UK, said: ‘Finding new ways to treat cancer that has spread is a critically important challenge for researchers around the world.

‘This study helps show that a new delivery system to release chemotherapy inside cancer cells could potentially make treatment safer and more effective.

‘More work is needed before we can tell whether or not it will work for cancer patients.’

Written by Fiona Macrae, Science Editor for The Daily Mail, March 14, 2016.

FAIR USE NOTICE: This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U. S. C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml“