Visceral photos show the fatal wounds Thomas Edison’s assistant sustained trying to help develop X-rays.

The first pristine image of bones beneath glowing flesh fascinated Clarence Dally in the 1890s.

The first pristine image of bones beneath glowing flesh fascinated Clarence Dally in the 1890s.

He had just become an assistant to Thomas Edison, the first X-ray image had just been produced by another scientist, by accident, and Dally was ready to make the awe-inspiring technology his life’s work.

Tragically, that work would also be his cause of death.

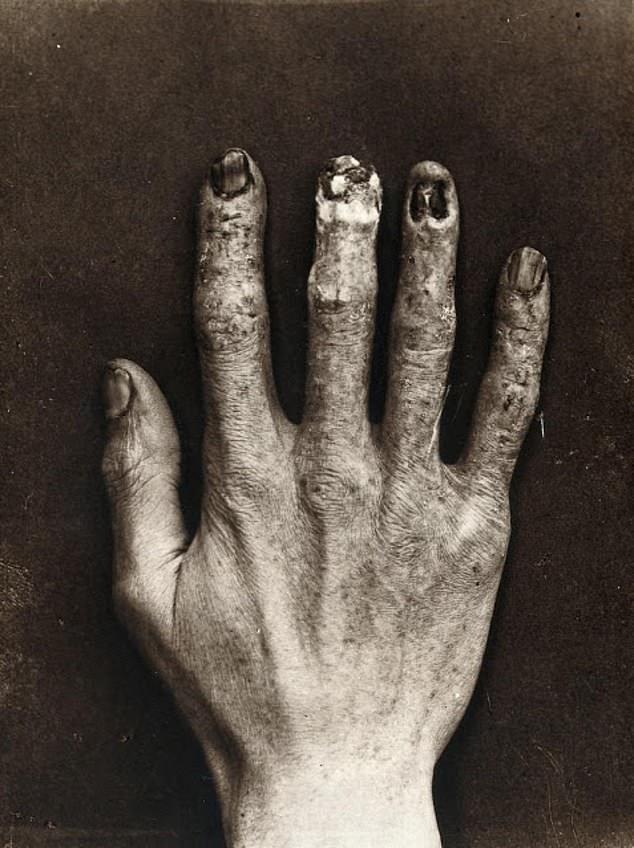

Dally exposed his hands to radiation over and over, for hours at a time, until melanoma bore holes in his hands – as documented in Edison’s gruesome photos – led to the amputation of both his arms and, ultimately, his death.

The hand of death: Clarence Dally’s hand was covered in lesions , looked burned and was falling apart after countless hours of intense X-ray radiation in Thomas Edison’s lab

Our curiosity and the allure of discovery have always enchanted humans.

Maybe that’s why Dally kept using his hands to test the X-ray he was helping Edison develop, long after they were in such constant pain he had to sleep with them in pales of water.

Maybe it’s why, according to Edison’s account, Dally always insisted on testing the strongest X-ray tubes, while Edison chose handle the less powerful ones.

Every year, doctors around the globe perform an estimated 3.6 billion X-ray exams, allowing them to precisely diagnose injuries and illnesses.

Countless lives have been saved by modern radiology, but these patients are only exposed to the short, intense waves of X radiation, and wear protection over the parts of their bodies that don’t need to be imaged.

The doctors and technicians that perform X-ray exams wear protection too, keeping their cancer risks at about the same level as anyone else’s.

That wasn’t the case for Dally.

Dally had just begun working with Edison when his inventor boss began experimenting with X-rays.

Dally had just begun working with Edison when his inventor boss began experimenting with X-rays.

Edison was not, however, the inventor of the X-ray image.

Through the scientific grapevine, he’d heard about the latest (accidental) triumph of Wilhelm Roentgen, a German physicist.

Roentgen had his lab records burned when he died, according to The Scientist, but the legend of his discovery of the X-ray credits his experiments with an ‘electron-discharge tube,’ which he noticed was casting a greenish glow through the glass and even black paper.

He realized that this never-before-seen form of radiation – which he dubbed ‘X,’ for unknown – could pass through materials other forms of light (including that emitted by Edison’s own incandescent bulb) could not.

With a lead sheet between the tube and his hand, which was in front of a screen covered in fluorescence, the screen glowed where his flesh was and was black where the bones of his hand would be.

Wilhelm Roentgen unintentionally invented the X-ray and captured the first such image. News of his discovery spread around the world after he published this photo of his wife’s hand

Shortly thereafter, he captured an X-ray image of his wife’s hand, which became world-famous – and got Edison’s attention.

Immediately, Edison was fascinated and wanted to experiment with this exciting new technology.

Of course, he too wanted to use a hand and its eerie bones as the subject.

But as the inventor observed and used his hands to work on the project, he himself couldn’t be the hand model.

So that task fell to Dally, who would leave his hands in the pathway of X-rays for hours on end while Edison tinkered.

Assistants – or ‘muckers,’ as Edison called them – worked grueling hours in his lab in West Orange New Jersey, sometimes spending 90 hours a week there, during many of which Dally was under the X-ray machine.

Edison did make advancements, developing the first fluoroscope, a screen through which he or the hundreds of people he demonstrated the invention to in 1986 could look and see bones beneath the flesh, in real time.

Fluoroscopes are still used to see moving X-ray images of the skeleton and solid organs.

But they are a minuscule fraction as powerful as what Dally would have been putting his hand under.

Some 100 years after the Edison’s invention, a scientist in the Netherlands found a device similar to Edison’s and discovered it delivered 1,500 times more radiation than a modern X-ray.

And it took 90 minutes to expose a single image.

So when Dally and Edison returned to West Orange and kept experimenting, the assistant went right back to subjecting himself to nearly unimaginable amounts of radiation.

Edison wrote letters and logs tracking his assistant’s deteriorating condition.

Edison looks through his invention, the fluoroscope, at his the hand of his assistant. Meanwhile, the assistant’s hand was being exposed to lethal doses of radiation

By 1900, we know the 35-year-old Dally was looking far older than his years. The left hand that he’d routinely rested under the X-ray machine was swollen, red and painful.

Sores started to creep up his hand and arm toward his face. His hair fell out.

So Dally switched arms, sparing the already mangled left one and exposing the healthier right arm to the powerful radiation instead.

Soon both hands hurt and burned constantly, so he soaked them in water overnight, just to cool them enough to sleep.

With the open lesions, this likely only made matters worse.

A couple of years later, doctors attempted to graft skin from Dally’s leg to his disintegrating left hand, but it was no use.

Finally it became clear that it wasn’t just lesions blighting the left arm, but carcinoma, skin cancer that, we now know, was almost inevitable given the incredible doses of radiation he was receiving.

Doctors amputated his left arm beneath the shoulder. Months later, according to Smithsonian.com, they took four of the fingers from his right hand.

Completely disabled, Dally could no longer work in Edison’s lab, but the scientist promised to support him for the rest of his life.

It wouldn’t be long.

In 1903, Dally’s right arm was amputated too.

The next year, he was dead, of metastatic skin cancer at age 39 – just eight years since he was first enchanted by an X-ray image.

Edison – whose vision had also been damaged by X-rays – was deeply shaken.

‘Don’t talk to me about X-rays,’ he said.

‘I am afraid of them.’

Written by Natalie Rahhal for The Daily Mail ~ June 28, 2019

FAIR USE NOTICE: This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U. S. C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml