What makes hospitals so deadly and how can we fix it?

Throughout COVID-19, abysmal hospital care and the suppression of effective off-patent therapies killed approximately a million Americans. Much of this originated from Obamacare pressuring hospitals to aggressively treat patients so they could quickly leave the hospital and reduce healthcare costs.

Throughout COVID-19, abysmal hospital care and the suppression of effective off-patent therapies killed approximately a million Americans. Much of this originated from Obamacare pressuring hospitals to aggressively treat patients so they could quickly leave the hospital and reduce healthcare costs.

More frail patients respond poorly to aggressive protocols, resulting in them frequently being pushed into palliative care or hospice. Sadly doctors are no longer trained to gradually bring their patients back to health, and hence view many of those deaths as inevitable.

In this article, we will review some of the forgotten medical therapies that dramatically improve hospital outcomes and highlight some of the key strategies patients and lawmakers can use to reduce hospital deaths.

Anti-vaccine graffiti is seen on the wall of a shop amid the outbreak of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) in Belfast, Northern Ireland January 1, 2021. REUTERS/Phil Noble

During COVID-19, we witnessed something previously unimaginable. A national emergency hospitalized thousands of Americans, where they were cut off from their loved ones and inevitably died. It soon became clear that the hospital protocols did not work, but regardless of how futile conventional care was, patients in our hospitals could not get the alternative therapies they needed.

This led to a sobering realization throughout America – what many of us believed about our hospitals was utterly incorrect. Rather than help patients, hospitals effectively functioned like assembly lines that ran disastrous protocols (e.g., remdesivir), denied patients access to their loved ones and refused to use alternative therapies even when it was known the patients were otherwise expected to die.

This was best illustrated by a travel nurse who who was assigned to the New York hospital with the highest death tolls in the nation and realized something very wrong was happening throughout the hospital so she covertly recorded it:

The Full Interview provides conclusive proof many patients were killed due to grossly inappropriate hospital protocols.

Appallingly, the COVID-19 treatment protocols financially incentivized remdesivir (“run death is near”) and then ventilator care but penalized effective off-patent treatments. As such, hospital administrators required deadly “treatments” like Remdesivir and retaliated against the doctors who used unprofitable treatments that saved lives.

Note: the NIH continued to make remdesivir the treatment for COVID-19 and forbid alternative therapies even as a mountain of evidence piled up its protocols. This was due to Anthony Fauci appointing the NIH committee and selecting chairs that had direct financial ties to Remdesivir’s manufacturer—a recurring problem in American medicine (e.g., I showed how our grossly inaccurate cholesterol guidelines were authored by individuals taking money from statin manufacturers).

Because of this murderous corruption, families began suing hospitals to allow the use of ivermectin for a relative who was expected to die (after being subjected to Fauci’s hospital COVID protocols). Remarkably, because there was so much money on the line, the hospitals chose to fight these lawsuits in court rather than just administer ivermectin.

Because of this murderous corruption, families began suing hospitals to allow the use of ivermectin for a relative who was expected to die (after being subjected to Fauci’s hospital COVID protocols). Remarkably, because there was so much money on the line, the hospitals chose to fight these lawsuits in court rather than just administer ivermectin.

Of the 80 lawsuits filed by lawyer Ralph Lorigo, in 40 the judge sided with the family, and in 40 with the hospital. Of those, in the 40 where patients received ivermectin, 38 survived, whereas of the 40 who did not, only 2 survived – in essence making suing a hospital arguably the most effective medical intervention in history. Yet rather than take this data into consideration, the profit-focused hospitals banded together to develop an effective apparatus to dismiss further lawsuits.

As I had expected something like this to happen, shortly before the pandemic, I put a home treatment plain into place (e.g., by procuring high-powered oxygen concentrators and non-invasive ventilation). Numerous people in my immediate circle were successfully treated at home, many of whom would have otherwise been immediately hospitalized and likely died.

Note: prior to COVID, we’d had other patients who merited hospitalization but simultaneously were likely to be put on the palliative care pipeline once admitted, so we’d already learned how to provide much of the care they needed at home.

Likewise, I also heard of more stories than I can count throughout the pandemic where a relative snuck an “unapproved” therapy to a patient in the hospital, saving the patient’s life.

~ Reductionist Realities ~

Every situation has two sides: the concrete factors and the intangible processes that lie between them. While modern science often focuses on optimizing the tangible, it tends to overlook the deeper essence of each phenomenon. However, those who nonetheless master these intangible aspects excel, as they solve a myriad of problems their peers cannot.

In medicine, this is clear in the contrast between algorithmic care – where doctors follow strict protocols – and the art of medicine, which involves critical thinking, individualized treatment plans, and nurturing the doctor-patient relationship, which is key to healing. Unfortunately, medical training has increasingly shifted from fostering independent judgment to prioritizing corporate-driven guidelines, leaving little room for the art of care.

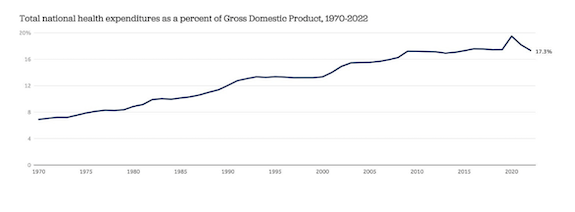

In tandem with this shift, the costs of American healthcare have ballooned:

Note: healthcare spending at the beginning of the 20th century was 0.25% of GDP.4

Most remarkably, despite spending 2-4 times as much on healthcare as any other affluent nation, the United States has the worst healthcare outcomes amongst the affluent nations.

This I would argue, is a result of our healthcare spending prioritizing what corporate interests want, not what produces effective healthcare and pervasive corruption being established throughout the government.

~ Economic Enticements ~

One of the most reliable means the government has to change the behavior of the healthcare system is by financially incentivizing the behavior it wants (e.g., pushing remdesivir).

A key part of this is grading hospitals on the quality of care they give patients and hospital reimbursement rates being tied to their “quality.” Unfortunately, while some metrics are helpful (e.g., what percent of patients get infected at a hospital), many other metrics lobbyists put in are not (e.g., what percentage of patients get vaccinated). As such, hospital administrators frequently force healthcare workers to push policies that harm patients.

Note: JCAHO is the main organization that assesses the quality of care hospitals provide. Hospital administrators in turn put great efforts into appeasing JCAHO.

After age 40, the amount of money spent on healthcare increases exponentially, with 22% of all medical expenses (and 26% of Medicare expenses) being spent in the last year of life. Since there’s always been a looming threat that Medicare (and Social Security) will go bankrupt, reducing those expenses has long been a focus for healthcare bureaucrats (as best as I can gather, this began in 1979 but really kicked into gear with Obamacare).

After age 40, the amount of money spent on healthcare increases exponentially, with 22% of all medical expenses (and 26% of Medicare expenses) being spent in the last year of life. Since there’s always been a looming threat that Medicare (and Social Security) will go bankrupt, reducing those expenses has long been a focus for healthcare bureaucrats (as best as I can gather, this began in 1979 but really kicked into gear with Obamacare).

The high cost of hospital stays – $2,883 per day on average, or up to $4,181 in California – has thus made reducing their length a priority for healthcare administrators. For example, hospitals are reimbursed with a flat fee per admission, regardless of how long the patient stays (causing hospitals to eat the cost of extended stays), and critical access hospitals (which get paid more) must keep their average hospital stay under 96 hours to maintain JCAHO and Medicare accreditation.

The high cost of hospital stays – $2,883 per day on average, or up to $4,181 in California – has thus made reducing their length a priority for healthcare administrators. For example, hospitals are reimbursed with a flat fee per admission, regardless of how long the patient stays (causing hospitals to eat the cost of extended stays), and critical access hospitals (which get paid more) must keep their average hospital stay under 96 hours to maintain JCAHO and Medicare accreditation.

Hospitals thus frequently pressure doctors to shorten stays through financial rewards or penalties for “excessive” stays, with committees aggressively scrutinizing and questioning any extended admissions.

Note: ER doctors’ decision-making on hospital admissions also varies significantly. Some are more cautious, admitting patients who may not be that ill to avoid liability, while others are selective, only accepting those with clear, severe conditions. These unnecessary admissions strain hospital resources and cause insurance companies to have unrealistic expectations for how quickly many conditions can recover and leave the hospital.

~ Time to Heal ~

Whenever a problem arises in medicine, the bureaucratic tendency is to find ways to micromanage the concrete variables at the expense of the intangible aspects of patient care. As such, almost all the protocols physicians are trained in (“to improve the quality of medical care”) tend to cast the intangibles to the side—to the point doctors are often penalized if they break from the protocols.

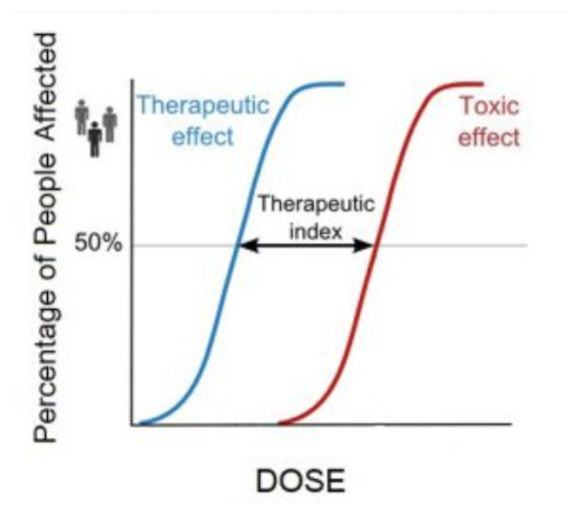

One area where this is particularly problematic is dosing, as different patients simply need different doses of the same therapy. For almost all therapies, a specific dose exists where most patients will begin to benefit from the therapy and another where they will begin to show toxicity.

In turn, doses are usually chosen by what’s in the middle of those two values (the therapeutic index). The problem with this is that since there’s so much variation in patient’s sensitivity to interventions, what can be a therapeutic dose for one patient is instead toxic for another. Since a standardized medical system can’t function without standardized doses, doses are used that frequently injure the more sensitive members of the population.

In turn, doses are usually chosen by what’s in the middle of those two values (the therapeutic index). The problem with this is that since there’s so much variation in patient’s sensitivity to interventions, what can be a therapeutic dose for one patient is instead toxic for another. Since a standardized medical system can’t function without standardized doses, doses are used that frequently injure the more sensitive members of the population.

Sister Sharon Falconer: “Heal! Heal!”

For instance, virtually every natural medicine system recognizes that “frail” patients typically cannot tolerate higher doses, and that treating them requires lower doses over an extended period of time. Unfortunately, since hospitals are “required” to get patients out quickly, higher doses are typically used, which causes those with more robust constitutions to recover rapidly, but instead overwhelms the frailer patients. Sadly, when this happens, their family members are often told, “Nothing can be done for the patient” or “They wouldn’t want to live like this for the rest of their life,” to pressure them to put their relative on palliative care to die “comfortably” or send them to hospice.

We believe this inappropriate dosing is a primary cause of unnecessary hospital deaths and that many “terminal” cases could recover with a slower course of treatment.

For example, in patients with congestive heart failure, they typically receive an aggressive diuretic regimen to get the excessive fluid out of the body. In more robust patients, this works, and you can discharge them within 2-3 days, but in weaker patients, it can set off a variety of severe complications (e.g., low blood sodium or kidney failure). For them, good outcomes can only be achieved with a 4-5 day hospital stay and a gentle, well-paced diuretic protocol.

Note: a similar issue happened during COVID with prematurely pulling patients off ventilators.

Because of these economic incentives, hospitals have gotten very efficient at moving patients through the palliative care pipeline, and hospital care often turns into a Darwinian situation where if you haven’t recovered in 3-4 days, you are ‘selected’ to pass away.

In short, hospitals are incentivized to “treat” patients with a standardized protocol rather than get them better. As such, many things that need to be done to improve patient outcomes aren’t, and critical resources are inappropriately diverted.

For instance, hospitals routinely invest in social workers to expedite patients’ discharge (e.g., by pressuring them). In contrast, nurses are so understaffed at hospitals that they often only have the time to take vital signs and give out the pills a doctor ordered, rather than examine each patient every few hours let alone become aware of what’s actually going on with them (which is often crucial for patient recovery). Ideally, nurses should be evaluating patients every 2-3 hours, and if slightly more money was spent to have 1-2 more nurses on each floor, it would be a relatively low-cost way to dramatically improve patient outcomes.

For instance, hospitals routinely invest in social workers to expedite patients’ discharge (e.g., by pressuring them). In contrast, nurses are so understaffed at hospitals that they often only have the time to take vital signs and give out the pills a doctor ordered, rather than examine each patient every few hours let alone become aware of what’s actually going on with them (which is often crucial for patient recovery). Ideally, nurses should be evaluating patients every 2-3 hours, and if slightly more money was spent to have 1-2 more nurses on each floor, it would be a relatively low-cost way to dramatically improve patient outcomes.

Ultimately, we believe the push to rapidly discharge patients from hospitals (e.g., nursing homes) rather than saving money actually increases healthcare costs because premature discharges frequently lead to numerous readmissions – which is particularly tragic since multiple hospital admissions often pull patients into a fatal downhill spiral.

Note: in contrast, accelerated hospital stays are much less of an issue for post-surgical patients because surgeons are financially penalized if their patients die within 30 days of surgery and hence incentivized to keep patients in the hospital for a sufficient length of time, illustrating how many things in medicine result from economic incentives rather than what’s best for a patient.

~ Training Priorities ~

This new paradigm is primarily a result of the younger doctors being trained to execute protocols and request consultations rather than critically examine each case, explore what they are missing, and try to calibrate their treatment plan to each patient (e.g., in the past medical training had a much greater focus on adjusting doses). Most strikingly, doctors are trained to accept the inevitability of many illnesses, which in reality (with the correct approach) are quite possible to treat.

To illustrate, I recently had a colleague whose father had been discharged to a hospice center and was started on palliative care because his case was terminal, but my colleague was (correctly) convinced he was just dehydrated and needed saline. Four days into this, they called me about it in tears and I asked, “Well you’re a doctor, can’t you get them to give the IV?” They replied, “The nurses will only do it with the hospice physician’s authorization, so I need help.”

To illustrate, I recently had a colleague whose father had been discharged to a hospice center and was started on palliative care because his case was terminal, but my colleague was (correctly) convinced he was just dehydrated and needed saline. Four days into this, they called me about it in tears and I asked, “Well you’re a doctor, can’t you get them to give the IV?” They replied, “The nurses will only do it with the hospice physician’s authorization, so I need help.”

Sadly, many doctors don’t even know they are failing their patients because the current training is based on the expectation hospital stays should be 3-4 days, and they never lived in the era before these mandates where it was possible to see the benefits of more extended hospital stays. As such, we must shift our focus away from optimizing the palliative care pathway and financially incentivizing patient survival rather than length of stay, as without those incentives, physicians will not be trained to save lives nor have the autonomy to do what’s best for their patients.

Note: preventing hospital readmissions (especially for those who have entered the downhill spiral) often requires effective integrative medical care outside of hospitals (another area where current medical education does not train doctors).

~ Life Saving Measures ~

At the turn of the 19th century, conventional medicine was rapidly becoming extinct because natural therapies were far safer and effective. To “save” medicine, the American Medicine Association ( ) partnered with the industry and the media to monopolize healthcare and eliminate all competition by declaring it quackery. As a result, between the 1920s to 1960s, many remarkable therapies (I regularly use in practice) were blacklisted and forgotten.

) partnered with the industry and the media to monopolize healthcare and eliminate all competition by declaring it quackery. As a result, between the 1920s to 1960s, many remarkable therapies (I regularly use in practice) were blacklisted and forgotten.

Many of these treatments initially gained their fame for the miraculous results they provided hospitalized patients on the brink of death.

For example, ultraviolet blood irradiation (UVBI) was remarkably effective for a myriad of infections antibiotics had failed (or couldn’t work on, such as viral pneumonia), and before long, doctors also discovered it was incredible for autoimmune conditions (e.g., asthma exacerbations), circulatory disorders (e.g., heart attacks) and surgeries (e.g., preventing infections, restoring bowel function, and accelerating healing). Sadly, once it took our hospitals by storm, the AMA blacklisted it (causing UVBI’s use to shift to Russia and Germany), and despite hundreds of studies showing its immense value (discussed here), it remains blacklisted by our medical system.

Note: UVBI is widely used in integrative medicine (due to its safe treatment of many different challenging ailments) and is one of the primary therapies I utilize.

Likewise, sepsis (which despite our “best” efforts, still kills 350,000 Americans each year) respond remarkably well to early IV vitamin C. Paul Marik for example, found it dropped his hospital’s sepsis death rate dropped from 22% to 6% (and in a study he showed it dropped the death rate from 40.4% to 8.5%20). Similarly, in the (rare) hospitals we’ve worked at that use IV vitamin C, sepsis deaths are extraordinarily rare. Yet, this approach is demonized, and it’s almost impossible to get it for a loved one in the hospital.

Recently, I’ve also begun bringing attention to another remarkable forgotten therapy, DMSO (e.g., it is arguably the safest and most effective pain treatment in existence – which in turn has led to thousands of readers sharing that DMSO got them their lives back). DMSO also effectively treats heart attacks, strokes, brain bleeds, traumatic brain injuries, and severe spinal cord injuries (areas where medicine struggles), and the evidence shows that were it to be adopted in our hospitals, DMSO could spare millions from a lifetime of disability or paralysis.

Note: many other options exist to optimize hospital care. For instance, we’ve found that IV amino acids dramatically increase one’s speed and likelihood of recovery, but in the hospital, they are only available in formulations (TPN) which also contain toxic seed oils and sicken rather than heal patients. Likewise, neglected off-patent therapies& allowed us to save critically ill COVID patients throughout the pandemic.

The Death of a Hospital

~ Conclusion ~

Because of COVID-19, the unconditional trust the medical industry made enormous investments to create and has relied upon for decades has been shattered (e.g., a large JAMA study of 443,445 Americans found that in April 2020, 71.5% of them trusted doctors and hospitals while in January 2024, only 40.1% did).

A question many insiders have asked me since the election has been, “What do we need to do to increase the survival rates of our hospitals?” I believe this is a critical lynch-pin of Making America Healthy Again. If clinical trials were to be conducted for the approaches detailed in this article (which the medical industrial complex has predictably always blocked), they would show an immediate and undeniable mortality benefit.

I sincerely hope our once in a lifetime political climate will create a window to try these forgotten approaches to hospital care, particularly since validating them in an acute setting will create an openness to using them for chronic illness, the area where they can most benefit humanity. I am profoundly grateful to each of you for helping to create this incredible chance to transform medicine for the better.

Written by a Midwestern Doctor for The Forgotten Side of Medicine ~ January 16, 2025