‘Yes, I’m messy, my mind is busy and I get flustered when I do admin. But to me it doesn’t matter — what matters is what I do about it.’

Prince Harry is the latest addition to the wave of celebrities who’ve been diagnosed with either ADD (attention deficit disorder) or ADHD (attention deficit hyperactivity disorder).

Prince Harry is the latest addition to the wave of celebrities who’ve been diagnosed with either ADD (attention deficit disorder) or ADHD (attention deficit hyperactivity disorder).

In fact, he was diagnosed in a highly public way, during a live-streamed conversation, by controversial self-help guru Dr Gabor Maté.

‘Reading the book, I diagnose you with ADD,‘ Maté said, referring to the Duke of Sussex’s autobiography, Spare. ‘I see it as a normal response to normal stress, not a disease.’

Other celebrities including Rory Bremner, Ant McPartlin, Heston Blumenthal and Sue Perkins have also recently revealed their diagnoses.

They join the estimated 3 to 4 per cent of UK adults with the condition, according to the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). And experts are reporting a skyrocketing of referrals in recent years.

Joanna Moncrieff, a professor of critical and social psychiatry at University College London and a practising psychiatrist, told Good Health: ‘In some mental health services, almost half the referrals are now for people requesting an ADHD assessment.

‘Many NHS trusts have such long waiting lists that people are turning to private clinics, where it can cost around £900 just for an initial consultation. And it’s extremely easy to get a diagnosis.’

Psychiatry UK, a private company contracted by the NHS to provide adult ADHD assessments, has seen referrals quadruple between 2020 and 2022 compared with the previous two years.

Symptoms of ADHD include inattention, hyperactivity and impulsivity.

Art student Sara was 16 when she was diagnosed with ADD (similar to ADHD but without the hyperactivity). She was doing badly academically, which she now attributes to being in a highly pressurised school.

Art student Sara was 16 when she was diagnosed with ADD (similar to ADHD but without the hyperactivity). She was doing badly academically, which she now attributes to being in a highly pressurised school.

I found it hard to focus or pay attention — it was a relief when I was diagnosed with ADD,’ she says. ‘At last people would no longer think I was being naughty or lazy. Everyone, including my parents, became more supportive.’

The treatment for ADD is similar to ADHD and Sara was prescribed methylphenidate (brand name Ritalin).

‘Although I could focus, the side effects were awful,’ she says.

‘I had heightened sound awareness: it felt like I could hear all the sounds around me piled into one — I felt overstimulated and that made me feel super anxious and overwhelmed.

‘I couldn’t sleep and turned to smoking marijuana to relax,’ says Sara, now 21, who is using a pseudonym.

‘I had no appetite. When a dose wore off, the effect was so severe that it felt like ADD times ten — I couldn’t focus, felt sluggish, and found it hard to string words together. I started smoking more marijuana to cope with the come-down and became addicted to it.

‘I stopped taking the tablets after six months, so sold the rest to my friends so that they could stay up all night at parties.’

Sara’s response to ADHD medication is not untypical. While some people swear they could not function without it, there is growing concern among experts that the explosive rise in ADHD diagnoses means many others will end up on drugs they don’t need, and they are not being warned of potentially serious side effects.

They may also find it hard to come off the medication.

NICE guidelines state people diagnosed with ADHD and ADD should be prescribed medication if their symptoms are causing significant impairment to their lives.

The drugs prescribed are stimulants, intended to boost concentration and focus. Four types are licensed in the UK for ADHD: methylphenidate, lisdexamfetamine, dexamphetamine and guanfacine.

‘As amphetamines, these stimulate the nervous system, increase your heart rate and levels of alertness — and are either identical or similar to the illegal drug speed,’ explains Professor Moncrieff.

‘They also produce a sort of tunnel vision, making you highly absorbed in what you are doing. They can help you to concentrate on simple things, short term, but haven’t been shown to improve performance in the long term.’

There has been an almost 85 per cent increase in the number of patients prescribed ADHD drugs since 2017 in England alone — with 646,000 items prescribed in October to December 2022; a 6 per cent increase compared with the previous quarter and a 69 per cent increase since 2017/18.

Professor Moncrieff says drugs prescribed for ADHD are similar to the illegal class-B drug speed, an amphetamine

This is prompting concerns about the drugs’ side effects.

‘They carry the same problems as recreational stimulants, with the risk of people getting tolerant to the effects, so they need higher doses,’ says Professor Moncrieff.

‘It’s widely accepted that they can cause dependence, insomnia and rapid weight loss, as well as producing withdrawal effects including fatigue and depression. Studies show an increased risk of heart complications such as heart attacks and strokes.’

The Ritalin product leaflet lists as ‘very common’ side effects: psychiatric disorders (27.8 per cent), insomnia (13.3 per cent) and irritability (11 per cent). ‘Common’ side effects include aggression, depression, decreased libido, panic attacks and changes in blood pressure and heart rate.

ADHD drugs are thought to stimulate the release of the brain chemical dopamine, which plays a role in motivation, mood, attention and memory.

Some experts argue that people with ADHD have a dopamine deficiency: the drugs act to normalise this.

Others disagree. Dr Sami Timimi, a consultant child and adolescent psychiatrist and author of Mis-Understanding ADHD, says: ‘Stimulants like Ritalin act on the nervous system in almost identical ways to cocaine. Like all other drugs we use in psychiatry, they have general effects on everybody. They do not correct any disease-based ‘chemical imbalances’.’

NICE figures suggest 5 per cent of UK children have ADHD — it’s feared many will inevitably end up on medication.

This worries Dr Timimi, who sees the drugs being overprescribed, and to ever younger children.

‘Six years old is meant to be the youngest you can prescribe stimulants, but I have come across it in children as young as three.

‘Six years old is meant to be the youngest you can prescribe stimulants, but I have come across it in children as young as three.

‘I see children who have become suicidal and psychotic as a result of ADHD meds,’ he says.

‘I had a 12-year-old who was hallucinating cartoon characters.

‘Many youngsters are prescribed a sleeping pill in tandem with the stimulant to offset the insomnia. It’s a long, difficult process to help them withdraw from both.’

There may also be significant long-term risks for children taking ADHD medication.

In 2007, a three-year follow-up of a famous U.S. study known as the MTA (Multimodal Treatment of ADHD) study, found children who used medication were significantly shorter, by an average of 2cm, and were an average of 2.7kg lighter than those who had not taken medication.

Separate research found adult patients prescribed psychostimulants such as methylphenidate over several decades had an eight-fold risk of developing neurological conditions including Parkinson’s disease, reported the journal Neuropsychopharmacology in 2018.

I am no stranger to the harmful side effects of prescription drugs.

I’m one of the 2 to 5 per cent of people with a life-threatening reaction to antidepressants known as SSRIs (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors).

In 2012, I had an adverse reaction and was lucky to survive. I later wrote a book — The Pill That Steals Lives — highlighting the then barely acknowledged fact that drugs such as antidepressants can have serious side effects, can cause dependence and in many cases are extremely hard to come off.

This is now being recognised: in 2020 the Royal College of Psychiatrists, acknowledging these problems, published a guide, ‘Stopping Antidepressants’.

But will we see history repeat itself when it comes to prescribing ADHD medications?

My fear is that with the rapid rise in ADHD diagnoses, people are being persuaded to take potentially dangerous drugs or give them to their children without being warned of the consequences.

Dr Timimi is also concerned: ‘More and more adults and young children are being convinced to take cocaine-like substances over a period of many years,’ he says.

‘As well as problems with dependence, once you give someone a psychotropic drug [i.e. one that alters perception and mood], it’s highly likely they will end up on more.

‘In the case of ADHD drugs, common side effects are depression and insomnia, with people seeking antidepressants and sleeping tablets to counterbalance these side effects.’

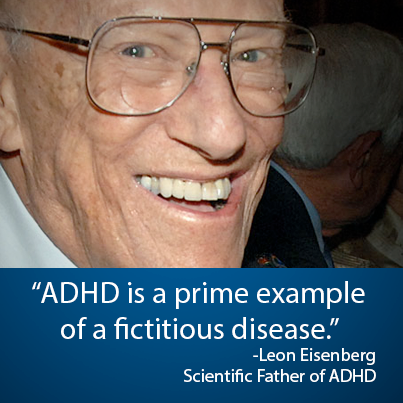

ADHD is a relatively new phenomenon, first ‘identified’ in the Eighties and included in the psychiatrists’ bible, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM).

‘ADD (attention-deficit disorder) with or without hyperactivity’ was introduced in the 1980 DSM-III; the label was further refined to ‘ADHD (attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder)’ in 1987.

ADHD is defined as ‘a persistent pattern of inattention and/or hyperactivity and impulsivity that interferes with functioning or development’.

Symptoms can be divided into two categories — ‘inattention’ and ‘hyperactivity and impulsivity’ — and include behaviours such as failure to pay close attention to details, difficulty organising tasks, excessive talking, fidgeting or an inability to remain seated in appropriate situations; these symptoms must be present before the age of 12 for a child to be diagnosed.

Symptoms can be divided into two categories — ‘inattention’ and ‘hyperactivity and impulsivity’ — and include behaviours such as failure to pay close attention to details, difficulty organising tasks, excessive talking, fidgeting or an inability to remain seated in appropriate situations; these symptoms must be present before the age of 12 for a child to be diagnosed.

There is a debate among experts as to whether some ‘new’ mental disorders, including ADHD, are real disorders or a cluster of behaviours that have been ‘diseasified’.

Dr Timimi is particularly concerned about the rise in mental health diagnoses for children and adolescents.

‘Labelling children’s irritating, worrying or distressing behaviours with a pseudo-medical label opens huge potential markets to prescribe dangerous and addictive stimulants,’ he says.

The first guidelines supporting the prescription of stimulants to treat ADHD were created by a British Association of Psychopharmacology team in 1997, chaired by David Healy, then a professor of psychiatry at University of Wales College of Medicine.

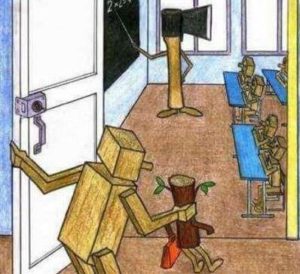

‘There were young boys who were hyperactive — it was thought that they would benefit from a low dose of a stimulant for a short period of time,’ says Professor Healy.

‘Some rise in hyperactivity may well have been because of a culture shift where schools were no longer able to absorb as much rough and tumble in the playground. The boys diagnosed with ADHD almost invariably grew out of this problem by their early teenage years.’

The idea that environmental factors could play a role in diagnosis is borne out by a 2011 study of one million children aged between six and 12, published in the Canadian Medical Association Journal.

The researchers were puzzled to discover that boys were 30 per cent more likely to be diagnosed if born at the end of the year rather than at the start; for girls, it was 70 per cent.

They concluded their behaviour was due to the fact some were 11 months younger than their classmates; the implication was that teachers and parents mistook immaturity for ADHD symptoms.

The same was found in other countries — the younger you are in your class, the more likely you will get an ADHD diagnosis.

It’s only relatively recently that adult ADHD has been recognised in the UK.

Previously, it was mainly diagnosed in young boys who couldn’t sit still in class — it was thought they would grow out of it.

Professor Healy says: ‘In 2010, 12 years after the guidelines had been written for young boys, I wrote to all 60 psychiatrists in North Wales and asked them if they believed adult ADHD existed. All said no.

‘When asked if they believed adult ADHD would exist in five years’ time, they all replied yes. They saw what was happening in the U.S., where pharmaceutical companies had been marketing the idea of adult ADHD since the late 1990s.’

Professor Healy has become increasingly worried by the U.S. situation.

‘There are now 30 different varieties of prescription stimulants available in the U.S.,’ he says.

‘In 2015-2016, 16 million adults (6.6 per cent of American adults) had tried a prescription stimulant.

Like me… Bored out of my Life in School.

‘Four hundred thousand (0.2 per cent) met the criteria for abuse of and addiction to those drugs — maybe that doesn’t sound like much and at the time this was about a quarter of those who reported addiction to opioids.’

He adds: ‘But while in the wake of negative publicity, opioid prescriptions have plummeted, prescriptions for stimulants have greatly risen — a 10 per cent increase in just the past year.’

Professor Healy has his own theory: ‘It tends to be extroverts who are diagnosed with ADHD. This is because they are naturally loosely-focused, creative, sociable and entrepreneurial.’

Transferring people’s natural differences into an illness is potentially dangerous, he believes.

‘We need variation in life just as in a football team we want people who can defend and people who can attack.

‘People are being told they have a broken brain and need to take a pill just because they are a defender being put in an attacking role. We need to celebrate variation without making it into an illness.’

Other experts say adult ADHD is not a character trait but a mental disorder that is under-diagnosed and under-treated.

Henry Shelford, CEO of the charity ADHD UK, said: ‘ADHD is a tough condition that has a significant effect on people’s lives. We shouldn’t demonise people for taking medication that is safe, effective and prescribed by specialists for a serious mental disorder.’

While the debate among experts continues, some people are finding alternatives to prescription stimulants.

Joseph Pack, a marketing director from Bakewell, Derbyshire, was 27 when he was diagnosed with ADHD in 2017.

Joseph Pack founded an organisation that sends a weekly newsletter with medication-free tips on managing ADHD

‘I left school with no GCSEs and always felt like an outsider,’ he says. ‘I couldn’t focus on important tasks — sitting in an office chair made me want to smash my computer screen.

‘I was really happy when I was diagnosed with ADHD — I felt understood, like I had a community. I was given Ritalin and it made me focused — but also very unsociable.

‘I ran a tech company and part of my job was to manage people — the drugs meant I could do boring admin tasks but sucked away my other skills.’

In fact, Joseph only took the methylphenidate tablets for two days.

‘To begin with I thought: ‘Wow, this is positive,’ ‘ he says. ‘But between doses the withdrawal was awful, like a gin hangover. It made me super anxious.’

Instead he found other ways to cope — cold showers, deep breathing and limiting working time to sessions of 25 minutes, with a five-minute break.

Joseph founded an organisation (drugfreeadhd.substack.com) that sends a weekly newsletter with medication-free tips on managing ADHD.

He’s contacted by people from all over the world who are experiencing the effects of prolonged use of stimulant medication.

Joseph says: ‘They say they can no longer work without the drugs so are hooked on Ritalin for life.

‘For others, ADHD drugs acted as a gateway to harder drugs. Last week I was contacted by a Canadian woman who gave her eight-year-old son Ritalin. By 15 he was crushing and snorting it.’

‘For others, ADHD drugs acted as a gateway to harder drugs. Last week I was contacted by a Canadian woman who gave her eight-year-old son Ritalin. By 15 he was crushing and snorting it.’

He’s now 41 and in rehab with a cocaine addiction — when his doctor stopped his Ritalin, he turned to an illegal drug to get a similar hit.’

Joseph is confident he has found a solution that works for him and many others.

‘The healthiest thing for me is to separate myself from a diagnosis a doctor once gave me,’ he says.

‘Yes, I’m messy, my mind is busy and I get flustered when I do admin. But to me it doesn’t matter — what matters is what I do about it.’

Novartis, the manufacturer of Ritalin, did not provide a comment.

Written by Katinka Blackford for The Daily Mail ~ April 11, 2023