Stocks plummet to the lowest point in 10 years.

Johnson & Johnson allegedly knew its Baby Powder contained asbestos for decades, a report claims.

Johnson & Johnson allegedly knew its Baby Powder contained asbestos for decades, a report claims.

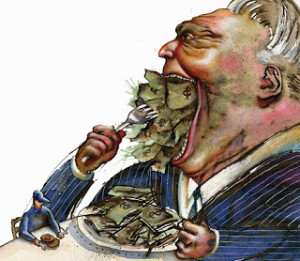

The firm has been forced to hand over thousands of internal, confidential documents amid lawsuits from 11,700 people, who claim the talc gave them cancer.

According to a Reuters investigation, the papers, dating from 1971 to the early 2000s, show J&J staff of all ranks – from executives to scientists to lawyers – knew that the powders sometimes tested positive for small amounts of asbestos.

Despite ‘frett[ing] over the problem and how to address it’ they failed to disclose their findings to regulators or consumers.

The damning Reuters report sent shares plummeting on Friday – closed out down more than 10 percent, the worst day in a decade.

It dragged down both the Dow and S&P 500, prompting global growth concerns.

The company released a statement Friday calling the Reuters article ‘one-sided, false and inflammatory.’

‘Simply put, the Reuters story is an absurd conspiracy theory, in that it apparently has spanned over 40 years, orchestrated among generations of global regulators, the world’s foremost scientists and universities, leading independent labs, and J&J employees themselves,’ the company said.

Shares plummeted 10 percent on Friday after the Reuters investigation was published, putting J&J on track to have its worst day in a decade The worst thus far was October 9, 2008, when J&J closed down 7.67 percent

The sharp drop, the biggest in a week (pictured), dragged down both the Dow and S&P 500 on Friday, prompting global growth concerns

WHAT THE DOCUMENTS SHOW

The earliest mentions of tainted J&J talc that Reuters found come from 1957 and 1958 reports by a consulting lab.

They describe contaminants in talc from J&J’s Italian supplier as fibrous and ‘acicular,’ or needle-like, tremolite.

That’s one of the six minerals that in their naturally occurring fibrous form are classified as asbestos.

At various times from then into the early 2000s, reports by scientists at J&J, outside labs and J&J’s supplier yielded similar findings.

The reports identify contaminants in talc and finished powder products as asbestos or describe them in terms typically applied to asbestos, such as ‘fiberform’ and ‘rods.’

In 1976, as the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) was weighing limits on asbestos in cosmetic talc products, J&J assured the regulator that no asbestos was ‘detected in any sample’ of talc produced between December 1972 and October 1973.

It didn’t tell the agency that at least three tests by three different labs from 1972 to 1975 had found asbestos in its talc – in one case at levels reported as ‘rather high.’

Most internal J&J asbestos test reports Reuters reviewed do not find asbestos. However, while J&J’s testing methods improved over time, they have always had limitations that allow trace contaminants to go undetected – and only a tiny fraction of the company’s talc is tested.

The World Health Organization and other authorities recognize no safe level of exposure to asbestos.

While most people exposed never develop cancer, for some, even small amounts of asbestos are enough to trigger the disease years later. Just how small hasn’t been established. Many plaintiffs allege that the amounts they inhaled when they dusted themselves with tainted talcum powder were enough.

HOW THE DOCUMENTS CAME OUT

The evidence of what J&J knew has surfaced after people who suspected that talc caused their cancers hired lawyers experienced in the decades-long deluge of litigation involving workers exposed to asbestos.

One of the first was Darlene Coker.

Coker knew she was dying. She just wanted to know why.

She knew that her cancer, mesothelioma, arose in the delicate membrane surrounding her lungs and other organs. She knew it was as rare as it was deadly, a signature of exposure to asbestos. And she knew it afflicted mostly men who inhaled asbestos dust in mines and industries such as shipbuilding that used the carcinogen before its risks were understood.

Coker, 52 years old, had raised two daughters and was running a massage school in Lumberton, a small town in eastern Texas. How had she been exposed to asbestos? ‘She wanted answers,’ her daughter Cady Evans said.

Fighting for every breath and in crippling pain, Coker hired Herschel Hobson, a personal-injury lawyer. He homed in on a suspect: the Johnson’s Baby Powder that Coker had used on her infant children and sprinkled on herself all her life.

Hobson knew that talc and asbestos often occurred together in the earth, and that mined talc could be contaminated with the carcinogen. Coker sued Johnson & Johnson, alleging that ‘poisonous talc’ in the company’s beloved product was her killer.

J&J denied the claim. Baby Powder was asbestos-free, it said. As the case proceeded, J&J was able to avoid handing over talc test results and other internal company records Hobson had requested to make the case against Baby Powder.

Hobson found a letter J&J lawyers had received only weeks earlier from a Rutgers University geologist confirming that she had found asbestos in the company´s Baby Powder, identified in her 1991 published study as tremolite ‘asbestos’ needles.

Hobson agreed to postpone his discovery demands until he got the pathology report on Coker’s lung tissue.

Before it came in, J&J asked the judge to dismiss the case, arguing that Coker had ‘no evidence’ Baby Powder caused mesothelioma.

Ten days later, the pathology report landed: Coker’s lung tissue contained tens of thousands of ‘long fibers’ of four different types of asbestos. The findings were ‘consistent with exposure to talc containing chrysotile and tremolite contamination,’ the report concluded.

‘The asbestos fibers found raise a new issue of fact,’ Hobson told the judge in a request for more time to file an opposition to J&J’s dismissal motion. The judge gave him more time but turned down his request to resume discovery.

Without evidence from J&J and no hope of ever getting any, Hobson advised Coker to drop the suit.

Coker never learned why she had mesothelioma. She did beat the odds, though. Most patients die within a year of diagnosis. Coker held on long enough to see her two grandchildren. She died in 2009, 12 years after her diagnosis, at age 63.

Coker’s daughter Crystal Deckard was five when her sister, Cady, was born in 1971. Deckard remembers seeing the white bottle of Johnson’s Baby Powder on the changing table where her mother diapered her new sister.

‘When Mom was given this death sentence, she was the same age as I am right now,’ Deckard said. ‘I have it in the back of my mind all the time. Could it happen to us? Me? My sister?’

Over time, lawyers in later cases knew from Coker’s, and other earlier cases, that talc producers tested for asbestos, and they began demanding J&J’s testing documentation.

What J&J produced in response to those demands has allowed plaintiffs’ lawyers to refine their argument: The culprit wasn’t necessarily talc itself, but also asbestos in the talc. That assertion, backed by decades of solid science showing that asbestos causes mesothelioma and is associated with ovarian and other cancers, has had mixed success in court.

In two cases earlier this year – in New Jersey and California – juries awarded big sums to plaintiffs who, like Coker, blamed asbestos-tainted J&J talc products for their mesothelioma.

A third verdict, in St. Louis, was a watershed, broadening J&J’s potential liability: The 22 plaintiffs were the first to succeed with a claim that asbestos-tainted Baby Powder and Shower to Shower talc, a longtime brand the company sold in 2012, caused ovarian cancer, which is much more common than mesothelioma.

The jury awarded them $4.69 billion in damages.

Most of the talc cases have been brought by women with ovarian cancer who say they regularly used J&J talc products as a perineal antiperspirant and deodorant.

At the same time, at least three juries have rejected claims that Baby Powder was tainted with asbestos or caused plaintiffs’ mesothelioma. Others have failed to reach verdicts, resulting in mistrials.

Written by Mia De Graaf for The Daily Mail ~ December 14, 2018

Show me de monee!

FAIR USE NOTICE: This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U. S. C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml“