I recently got into an argument, again, about cancer. The occasion was a talk by one of my colleagues at Stevens Institute, philosopher Gregory Morgan, on the fascinating history of research into cancer-causing viruses.

I recently got into an argument, again, about cancer. The occasion was a talk by one of my colleagues at Stevens Institute, philosopher Gregory Morgan, on the fascinating history of research into cancer-causing viruses.

The occasion was a talk by one of my colleagues at Stevens Institute, philosopher Gregory Morgan, on the fascinating history of research into cancer-causing viruses. In the Q&A, someone commented on how far science has come in understanding cancer’s causes.

With my usual kneejerk negativity, I lamented that all our knowledge about oncogenes, oncoviruses and other cancer catalysts has not translated into significant reductions in mortality.

Others in the audience objected that they knew people whose lives had been saved by better tests and treatments. They expressed incredulity when I said that cancer tests and treatments might be hurting more people than they helped.

So I thought I’d assemble some basic facts on this issue, especially since that gives me a chance to draw attention to excellent new books–by journalists Dan Fagin and George Johnson, two old friends–that underscore cancer’s persistent intractability.

I’ll get to Fagin and Johnson soon, but first some background information. Cancer journalism usually hails alleged advances, but in 2009 Gina Kolata of The New York Times provided a blunt reality check, “Advances Elusive in the Drive to Cure Cancer,” that five years later remains all too relevant.

Kolata asserts that “the grim facts about cancer can be lost among the positive messages from the news media, advocacy groups and medical centers, and even labels on foods and supplements, hinting that they can fight or prevent cancer.”

Kolata asserts that “the grim facts about cancer can be lost among the positive messages from the news media, advocacy groups and medical centers, and even labels on foods and supplements, hinting that they can fight or prevent cancer.”

In 1971, she recalls, President Richard Nixon declared war on cancer, vowing that the disease would be cured within five years. Since then, the National Cancer Institute has spent $105 billion on research, and other institutions—private, public and non-profit–have spent many billions more.

Kolata acknowledges some genuine advances, noting that “a few rare cancers, like chronic myeloid leukemia, can be controlled for years with new drugs. Cancer treatments today tend to be less harsh. Surgery is less disfiguring, chemotherapy less disabling.”

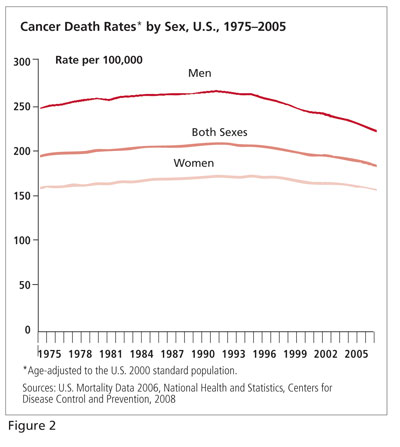

But the overall death rate for cancer—adjusted for the aging of the U.S. population—has fallen by only five percent since 1950, Kolata points out. During this same period, the death rate for heart disease plummeted 64 percent and for flu and pneumonia 58 percent.

The decline in the cancer mortality rate since 1950 has not been steady. The rate actually increased from 1950 through the early 1990s and then began dropping. In other words, the mortality rate rose for two decades after Nixon’s declaration of war before dipping downward.

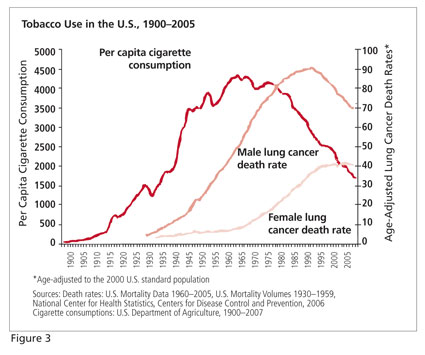

The decline in mortality rates since the early 1990s has been credited to improved tests and treatments, but Kolata tossed cold water on these claims last year. “The much touted recent drops in some cancer rates,” she writes, “were mostly attributable not to cancer breakthroughs but to a decline in smoking that began decades ago–propelled, in part, by federal antismoking campaigns that began in the 1960s.”

This view is corroborated by a 2010 Skeptical Inquirer article, The War on Cancer: A Progress Report for Skeptics. Reynold Spector, professor of medicine at Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, provides charts (which I have reproduced) showing how a rise and fall in smoking preceded the rise and fall of the death rate from cancer, and particularly lung cancer. Citing Kolata’s 2009 article, Spector agrees with her that “the war on cancer has not gone well.”

Cancer-research boosters often state that people are surviving cancer for longer periods. But that is because men and women are being screened more frequently with higher-resolution tests and hence being diagnosed with cancer at earlier stages. They are living longer after diagnosis, not living longer in absolute terms.

Cancer-research boosters often state that people are surviving cancer for longer periods. But that is because men and women are being screened more frequently with higher-resolution tests and hence being diagnosed with cancer at earlier stages. They are living longer after diagnosis, not living longer in absolute terms.

Spector explains: “First, if one discovers a malignant tumor very early and starts therapy immediately, even if the therapy is worthless, it will appear that the patient lives longer than a second patient (with an identical tumor) treated with another worthless drug if the cancer in the second patient was detected later.”

Indeed, as I have reported repeatedly on this blog, most recently in February, there is an emerging scientific consensus that mammography, the PSA (prostate-specific antigen) blood test and other screening methods have been overprescribed—and often lead to unnecessary treatment.

Men diagnosed with prostate cancer because of a PSA test are 47 times more likely to get unnecessary, harmful treatments—biopsies, surgery, radiation, chemotherapy—than they are to have their lives extended, according to one recent study. Another found that as many as 33 women diagnosed with breast cancer after receiving mammograms receive unnecessary treatment for every woman whose life is saved.

Last year a group of oncologists acknowledged that Americans are being over-tested and over-treated for cancer. These problems have led to calls for more emphasis on prevention—and that brings me to the books of Fagin and Johnson. Both books, to different degrees, raise questions about how far we can go toward preventing cancer by identifying carcinogens and expunging them from our environment.

This year Fagin won a Pulitzer Prize for his book Toms River: A Story of Science and Salvation, about a New Jersey town ravaged by industrial pollution. The meta-theme of Fagin’s book is how extraordinarily difficult it can be to trace cancer clusters to specific environmental factors, even the kind of egregious pollution produced in Toms River.

The linkage of cancer to tobacco smoking was a triumph of epidemiology that has been hard to replicate, according to Fagin. Noting that public-health investigators eventually showed that children in Toms River had an elevated rate of cancer, Fagin remains cautiously optimistic that epidemiology can produce worth-while results, which can guide prevention efforts.

But in a review of Fagin’s book for Slate, Johnson suggests that even the small surplus of cancer cases in Toms River might have resulted from chance. “Each year,” Johnson writes, “about 1.6 million cases of cancer are diagnosed in the United States, and epidemiologists regularly hear from people worried that their town has been plagued with an unusually large visitation. Time after time, the clusters have turned out to be statistical illusions—artifacts of chance.”

Even the famous Erin Brockovich incident has been “debunked,” Johnson says. “Hexavalent chromium in the water supply of a small California town was blamed for causing cancer, resulting in a $333 million legal settlement and a movie starring Julia Roberts. But an epidemiological study ultimately showed that the cancer rate was no greater than that of the general population. The rate was actually slightly less.”

In his 2013 book The Cancer Chronicles, Johnson depicts cancer as a consequence of entropy’s inexorable but unpredictable degradation of our extraordinarily complex genetic underpinnings. It is not surprising, he says, that attempts to link cancer to specific environmental factors have produced slim results.

Just last month, Johnson reported in The New York Times that there is little evidence that we can reduce our risk of cancer by eating certain foods and avoiding others.

“About all that can be said with any assurance,” Johnson writes, “is that controlling obesity is important, as it also is for heart disease, Type 2 diabetes, hypertension, stroke and other threats to life. Avoiding an excess of alcohol has clear benefits. But unless a person is seriously malnourished, the influence of specific foods is so weak that the signal is easily swamped by noise.”

Cancer has killed people I love at an early age, so I am as desperate as anyone for progress. Sometimes I feel like a jerk when I tell people how little progress we’ve made, especially after they tell me stories about loved ones who have triumphed over cancer. But if we are to have any chance of overcoming this terrible disease, we must face it squarely.

Illustrations: Reynold Spector and Skeptical Inquirer.

Written by John Horgan and published by Scientific American ~ May 21, 2014

FAIR USE NOTICE: This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U. S. C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml“

FAIR USE NOTICE: This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U. S. C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml“